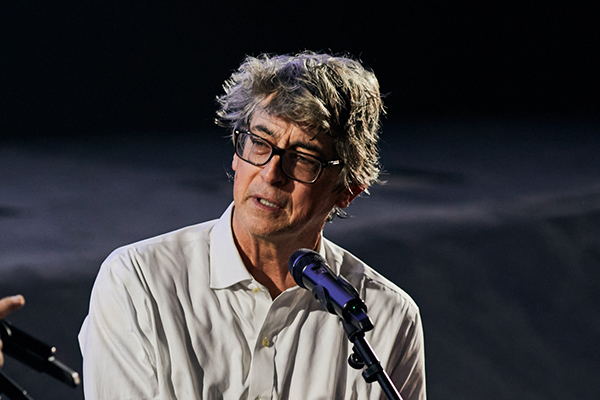

Alexander Payne

“Cinema is a miracle!”

Posted on 16.10.2023

"What is a master class anyway?" asked American filmmaker Alexander Payne with a touch of irony at the start of his conversation with the audience at the Pathé Bellecour. Afterwards, for more than 90 minutes, the director of Sideways gave a detailed account of his working methods and reminded us that cinema is nothing more than "a mirror of our existence".

© Léa Rener

© Léa Rener

On how his cinephilia has influenced his directing:

First of all, I have to say that I was lucky enough to meet Pierre Rissient, Bertrand Tavernier or even Martin Scorsese, people whose cinematographic culture totally crushes mine. We've all stolen shots from directors whose films we've loved, or scenes that have made an impression on us. Why should I stop myself from using them? I believe that any outside help is welcome in the making of a movie. Having said that, I've seen a lot of movies but most of the time, when it comes to making your own film, you're on your own. You are alone.

On the influence of the 1970s on his films:

Like all of us, I've seen films from all over the world, but I was a teenager in the 1970s! The culture we're exposed to imprints itself on us and marks us for life. I was a film buff, I went to the cinema every week, and I saw pictures that are now considered to be part of a certain golden age of American cinema. But I had absolutely no idea. At the time, these movies were presented to us as mainstream commercial features. When I left film school, the culture changed, but I remained the same. So I started making films very much inspired by the 1970s and I'm still doing that.

On his characters:

What viewer is interested in perfect characters? Mine are far from perfect. We love gangster films, and yet the characters are killers. Secondly, I believe that every director operates according to patterns that they repeat indefinitely, unconsciously. Why, for example, did Chaplin always write about homeless people? We all put ourselves into our protagonists. For example, Chekhov, who I draw a lot of inspiration from, developed very caricatured characters at the beginning of his career and made fun of them. The older he got, the more he deepened his relationship with his characters. I think that with age, we gain depth and we analyse our characters better. You learn to write them differently.

On the theme of the family, which figures heavily in his films:

I don't know why it's so prevalent. It's probably a very unconscious process on my part. But look at all the films that feature it, first and foremost The Godfather... When I'm making a film, I attach a great deal of importance to places and I like to take a documentary approach to fiction, from the moment I write the script, as far as the emotions of the characters are concerned. If artificial intelligence could create good scripts for me, I'd be very happy!

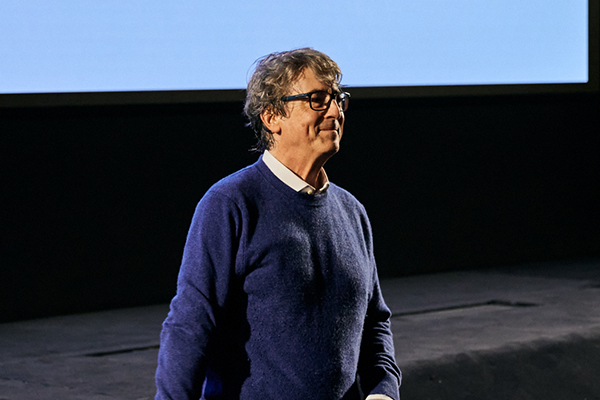

© Léa Rener

© Léa Rener

On his approach to politics:

I approached it in a very realistic way, of course, but it was more the social aspect than the actual politics that interested me. I studied it more from a humanist and class struggle point of view. I like to see how they clash on that spectrum. My first two movies were the most political I ever directed.

On Sideways, the movie that changed his career:

I wasn't aware of its success. I think I just couldn't believe it. In general, a director sees success as a good thing, because it means he can go on and make other films! But I had a very small-town side that advised me not to get carried away and to keep my feet on the ground.

On how he gets new things out of his actors:

Movie stars like to be seen not just as movie stars, but also as actors. I never write a role for an actor, whether he's a movie star or not, but I invite the actor to embody the role, which is different. Maybe that's the right solution: don't think of actors as stars. For me, two things are very important: the script and the acting. And in that respect, the cast has to be good. For Sideways, Brad Pitt, Edward Norton and George Clooney wanted to make the film. Their presence would have enabled me to get more money to finance it. But in my eyes, they weren't the right choice for the part! What I'm most proud of is directing anonymous, non-actors. It takes time, but it's great fun. In Nebraska, the farmers really play themselves. Finding a documentary aspect to my films allows me to give them a fabric of reality.

On the endings of his films:

There are two or three tricks to remember if you want to end a movie successfully. Generally, when you're struggling to conclude a film, the easiest way is to remember the beginning and repeat an element. For example, Sideways begins with a character knocking on a door and the film ends that way. Secondly, we're often taught in screenwriting classes that you have to work on the character's catharsis, to show how much he's changed. Personally, I don't believe in that very much. You never change, fundamentally!

On finding funds for movies:

It's always difficult to find funding. You can always criticise investors for no longer allowing certain types of films to be made, but you also have to blame directors for no longer offering them. My name now allows me to get funding, but only up to a certain limit. The budget for Nebraska dropped from 16 million dollars to 12 million dollars when I said I wanted to shoot it in black and white. As for About Schmidt, 16 million dollars of the 32-million-dollar budget went directly into Jack Nicholson's pocket! Now people are asking me if I'd like to direct a series. Of course, I'd be very happy to, but I'm a guy who thinks about my work in the cinema first!

On his love of cinema:

I'm happy to have been born into a world where cinema exists. One of the functions of art is to mirror our existence. Cinema is a miracle! The most wonderful art that life has given us. The only thing I knew for sure was that I wanted to make comedies. As for the rest, it was impossible to predict anything. My instincts have dictated my choices.

Reported by B. P.